The ‘father’ of modern notation

Guido d’Arezzo, the Benedictine monk pictured above, has been lauded as a great contributor to the development of Western musical thought—especially where it relates to the notation of music. Some of his contributions were quite revolutionary for the times in which he lived. He offered alternatives to the musical status quo of the period. A very opinionated and outspoken fellow, he eventually parted from the Pomposan abbey in which he began his explorations of musical theory after developing irreconcilable views on music. In parting, Guido left to share his works in an attempt to remedy the shortcomings of how music was studied and practiced during his lifetime.

Musical neumes

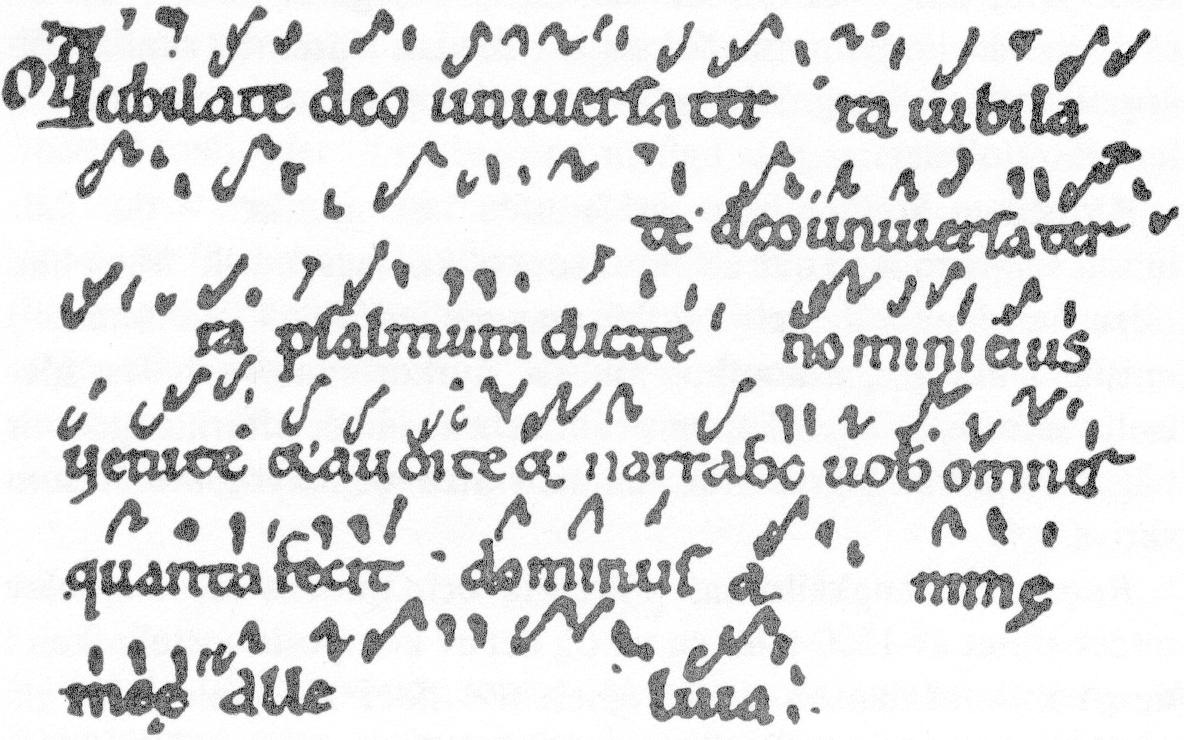

The prevailing method of written music for much of Guido’s life was a system known as neumatic notation. These staffless neumes were a form of writing employed particularly in the religious setting for hymns and other religious songs. Neumes themselves offered little more than a general guide to the singer as to the changes in pitch between the words and syllables they were singing. Though the best of many attempts made to codify music for the times, these neumes had a major shortcoming: they never indicated the actual notes to be sung. The key and notes had to be memorized by the singer before the use of neume could provide any sort of value. This meant that the song must be taught to and memorized by the singer before they could ever attempt to sing from neume.

You may be thinking, if a singer had to both learn and memorize the song before attempting to even look at the neume, what was the point? Well, the neume themselves can be seen as a short-term solution to the issue plaguing singers of the time; namely, they couldn’t perfectly remember all the songs they had memorized and needed some form of guidance. At a glance, the above excerpt from a neumatic manuscript illustrates how confusing this system of notation was. Different breaths, pitch changes, and rhythms all had their own unique scribble shapes above the lyrics.

A singer wouldn’t necessarily know what note to sing even if they knew how the phrase moved based on the indications. There was no way to derive the note that needed to be sung in this way of recording music. They implied the direction of the next note in relation to the current one, higher or lower, a rise or fall or other similar embellishment. That was why singers were so reliant on their teachers imparting that information directly via performance and memorization.

Needless to say, this form of notation fell very short of preventing errors in singing, often from misinterpretation or a singer’s faulty memory—leading to many wrong notes ringing out. Discordances within holy songs?! Blasphemy.

Guido, a musical teacher and choir leader, sought to remedy this problem he observed. His remarks sum up well the issues with this prevailing method of notating music of the time:

“Singers are, in our day, the silliest of all men. In every art there are a few to whose understanding we may appeal, but to the greatest part there are more who must learn with the aid of teachers. Once the boys have read through the Psaltery then they could read all other books. People of the country learn very soon the knowledge of land management. For we evaluate a vineyard, we plant a tree, we know how to pack a donkey; what would apply in one case applies in all other cases.

But particularly our singers and singing teachers, if they were to sing daily for a hundred years could not sing without a teacher a single antiphony, while they waste such time with their singing that they could learn completely all worldly and spiritual knowledge.”

—Guido d’Arezzo: Prologus in Antiphonarium

Outspoken as he was, his opinions ruffled many feathers within his abbey and elsewhere—perhaps because there was truth in his observations that many did not want to concede. There is always resistance to change, after all. Guido ultimately left the Abbey of Pomposa, moving on, perhaps, to bigger and better things. His inventions also drew the attention of prominent church figures, such as the Bishop of Arezzo who employed him to continue his work after he departed the abbey in Pomposa.

The four-line staff

Many attribute the invention of the four-line staff directly to Guido. There are equally as many who propose that, while he may have employed and advocated for the use of the four-line staff, it was not of his invention entirely. In his work entitled, Prologus in antiphonarium, Guido argues for the use of this new means of writing and reading music, proposing that it is a solution for the dissenting opinions of singers, both student and teacher, over which notes may fall where—eliminating the confusion the prevailed in either fault of memory or in the reading the other forms of neumatic notation.

Either way, his intention of advocating for its use was aimed at utility and freedom. He desired to free singers from the burden of needing to be taught and learn each song before they could attempt to perform them. What if they could learn to read music once, and employ that knowledge when reading any song? Wouldn’t that be a liberating thought? He claimed his students, employing his method, could master in 5 months what it took a singer of the time many years to accomplish. It’s easy to see why some of his counterparts might have condemned Guido’s revolutionary methods, and though he had a habit of being blunt, he also had a habit of telling the truth.

Pope John XIX even summoned Guido to Rome to demonstrate this newly devised way of reading music. The Pope was not satisfied until he was able to recite a piece of music previously unknown to him via sight reading—successfully employing Guido’s new methods. Guido traveled around Europe, some suspect even as far as England, to share his methods of instructing music. Here is an example of a four-line staff of which he was such a large proponent:

Guido’s work is the first recorded instance of using the four-line staff, which is why he is often most widely attributed to its development. Whereas the neumes that existed prior to Guido’s time focused primarily on the organum, or plainchant, this new method was also easily adaptable to instruments as well—making it a significant addition to the advancement of music. While the notes themselves still look quite different from what we’re used to in today’s written music, it is still quite clear that it is a giant step closer to modern notation than the previous example of the staffless neume shown above.

When it comes to Guido d’Arezzo and his many contributions to the advancement of musical thought, I’ve but barely made a dent in covering this singular topic. If you are interested in learning more about this interesting individual, fear not, I’ve got a couple more topics to discuss in future posts! For now, I’d like to wish you all a happy 2024 and sign off. It shall be a great year for exploring early music!

—Collier

This was great! I loved the part about Pope John XIX - that was new to me.